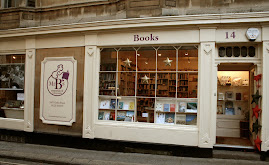

Mr B's Tremendous Tuesday Book Group read A.L.Kennedy's "Day" shortly after it had won the 2007 Costa Book of the Year Award. Mr B had an e-chat with the author to get her answers to some questions posed during the book group discussion. Everyone at Mr B's would like to thank Alison for answering the questions for us and Chloë at Random House for making this interview possible:

Mr B - Alfred is portrayed as a flawed character but does he actually have many real flaws? As a group we ended up thinking that he isn’t really as flawed as he’d have us believe (as shown by how much others – Skip, Pluckrose etc – seem to value him). Other than being prone to murder of course!

A.L.K - Yes, murder is a bit of a drawback, but he is very specific in his murdering. Unless you look at the morality of area bombing - which I think he has become more troubled by as time has passed and he's talked to Ivor. But he is, as you say, a man that others can warm to. I think he's very loyal to his friends and can be very loving. He would probably assume that someone he loves will die - which would disturb him - and he'd be aware that his nerves are very frayed, so he's not that good at strangers, or loud noises, or stress. And I would imagine he gets into, at least verbal, fights quite easily. But generally, a decent man doing his best in odd circumstances.

Mr B - The structure of the book and the way we follow Alfred’s thought-processes back to his four or five memory areas (the crew, his family, the bookshop, Joyce etc) caused lots of discussion. I think the biggest question we had for you as an author was where did you start once you’d decided to use that style? Did you write the book in a very different sequence to the end-result?

A.L.K - I wrote the book in the sequence you meet. If you think about it the chronology just happens to be emotional rather than temporal - it's still a chronology. We go from early to late in what he remembers (that's completely conventional really) and from intimate to less intimate, depending on what he can stand to feel. When I set out, I only had an idea of who Alfred was and what he could stand to think about. I knew he wouldn't open up early and that the frame of the piece was based in the fake POW camp. Everything really came from Alfred and the fact that WWII was enormous - then I worked out from there. It took about 3 years to prepare, so I had a while to think.

Mr B - Another point that came out of the structure was that people had found they really had to concentrate hard in the first few chapters in order to follow the flitting of Alfred’s thoughts between times and story areas that they were not yet familiar with. Then, as you get to know Alfred and his references better, it becomes “easier” to follow. Did you set out to immerse your readers immediately into Alfred’s viewpoint and were you conscious that the early pages may make more difficult reading than the later ones as a result?

A.L.K - I do tend not to compromise when I open up a book and I thought with this one - because I have to take you so far into somewhere really unpleasant, it would be best to get you used to concentrating and trying to reach Alfred and go with him - so when people start dying and bombs start droping you're going to be there for him. With a 3rd person book that covers so much ground it seemed a way to create as much intensity and intimacy as possible - given that intensity would define most of his wartime experiences.

Mr B's - We were intrigued by Joyce’s relationship with Alfred. She seemed quite a predatory character and some people wondered what she saw in him? What do you think attracted Joyce to Alfred?

A.L.K - I always liked Joyce, but I couldn't really bend the book out of shape to make it about her as well - Alfred does love her but he just has so much else on his mind. I think Joyce was in a very hard position - she clicked with Alfred (these wartime romances often did fire up very quickly) but she was married to someone who was almost certainly dead and whom she had married in haste. She seems to have socialist leanings and to be keen to escape her own set. She knits for him, which I think is an indication of something - clearly she's an awful knitter. I managed to allow her to explain herself a little at the end - how difficult it was effectively waiting for two people and knowing so little about what would happen. She's a bit fast, but I think she would try her best for Alfred and their relationship might work.

Mr B - One of our book group members thought that the overriding message or moral of the book might be in Ivor Sand’s monologue near the end of the book where he talks about people not being scum. Is there an overriding message and if so what would you say it is?

A.L.K - My overriding message is always that people aren't scum - although I very rarely have someone around like Ivor who lectures and can say such things. There's a sense of the complication and awfulness of war - that human potential can be appalling and war releases it - that guilt is difficult and justice can fail. But I'd be happy with "people aren't scum" yes.

Mr B - The group were interested in your motivations behind writing the novel. The tagline on the reverse of the book praises the book “particularly” because it’s written by “a woman born in 1965”. Did you set yourself the challenge of writing a novel about WW2 and then create the character and decide to follow his story, or did you start with Day as a character and then choose to place him in a WW2 setting? Or something else entirely?!

A.L.K - The impetus for the book came from 3 areas. 1) I've always been interested in that period and I worked for quite a while in elderly care homes and just think that generation was remarkable. 2) I was preparing the book while we ploughed off into a very different war, still pursuing the idea that area bombing is acceptable and practical as a war policy. I wanted to look at the moral ambivalnec of even a just war, while we pursue an unjust war, betray the war time generation who gave us the welfare state and follow policies which, in some cases, are the reverse of WWII's "what we're fighting for" 3) I read a 1949 magazine article about the filing of the movie "The Wooden Horse" - using former POW's as extras. I wanted to know why someone would go back in that way and what would happen when they did. Other people's ideas of what male or female people should write or what age they should be... all those things don't really interest me. If an idea arrives, it's my job to serve it as well as possible - to prevent the ideas behind it from going elsewhere.

Do let us know what you think of the book and the author's answers by adding a comment. If you haven't read it yet, you can buy a copy of "Day" from Mr B's by clicking HERE.